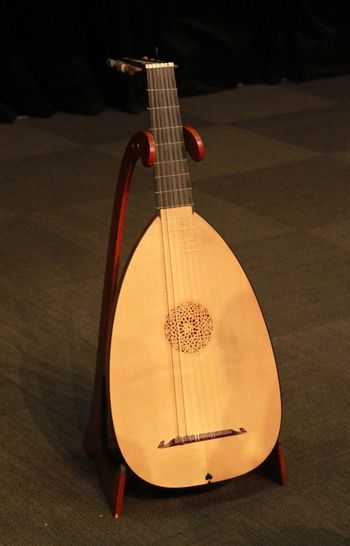

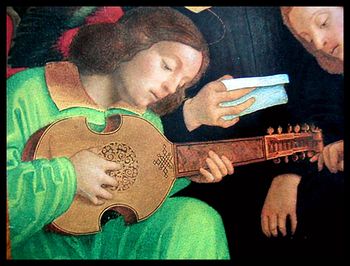

Some people would ask why I have named my album "Renaissance and Baroque Guitar", when there was not an instrument called a 'guitar' in the Renaissance. In my opinion it's not about what it's called, but all about the number of strings (or courses of strings.) Like the guitar, the Renaissance lute and vihuela were 'six string' instruments (strung in double courses of the same pitch. Well, most of the time). The strings on these early instruments were made of gut. Double course gut strings necessitate a different playing technique compared to the modern guitar. These early instruments have a charming sound. But again, it's about the number of strings! (well, courses of strings of course). On these instruments, the way the music is played (fingered), with the left hand, is very distinctive. Change the fingering and you alter the music dramatically. So, as the modern guitar is a 'six string' instrument, it is possible to play this early music retaining the basic fingerings of the composers, and thus the intent of the music. (That is, if you tune the third string to F#). How about we just forget about this, Renaissance lute and vihuela is guitar music. However... Baroque lute music is not 'guitar music,' because Baroque lutes had up to thirteen courses. I avoid playing Baroque lute music on the guitar. However, in the Baroque period, there was an instrument called 'guitar'. The Baroque guitar was a five course instrument with courses not always tuned of the same pitch. But ironically, as a five string instrument, it's less like a guitar than a Renaissance lute or vihuela. I think we're getting the picture that there has never been much consistency in these guitar-like instruments (the guitar included). The moral of the story: If the piece works, play it. How about we just talk about my guitars now.

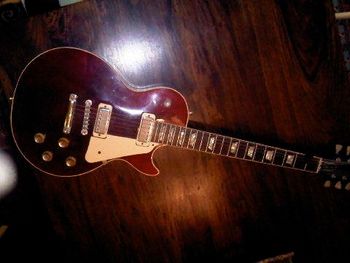

I am very fortunate to have stumbled my way into some really good guitar purchases early in my life. It started with the purchase, at age sixteen, of a 1972 Gibson Les Paul Delux at a mall in Savannah, GA. Somebody had traded it in for an organ, and the keyboard players in the shop didn't know what it was. Nor did I, at that age, because I thought $200 was a lot of money! My luck continued with a classical guitar purchase in the '80's, and one in the '90's, before good wood became scarce and prices escalated. A good concert guitar these days will go for at least ten thousand dollars. Over the years, I always assumed my guitars were just OK, compared to the amazing and rare instruments the pro's must be playing. Not so! Unbeknowst, I had made two very good guitar purchases in my youth.

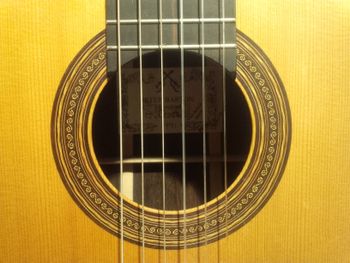

1984 Ramirez 1a 'De Camara'

My first purchase, in London in about 1985, (when I was very, very young), was a 1984 Jose Ramirez 1a, 'De Camara' model. I paid one thousand pounds for this guitar. Yes, a lot of money! Well, it's worth many thousand now. Jose Ramirez is the most famous guitar shop, which defined the Madrid style: These are large bodied, heavy guitars with smooth sounding basses and good projection. They produce a dark, mysterious sound. My Ramirez has a cedar top, which gives it a nice warm sound. It is also unique in that it is a 'de camera' model. It has an inner shelf which adds clarity and separation to the notes. Little did I know when I bought this guitar, that it was the ideal Ramirez to record on, particularly for Renaissance and Baroque music in which polyphony can get lost in the moody depths of a standard cedar guitar.

For this album I used this guitar on the Dowland fantasia, the De Visee bouree and gigue, Fantasy XIV by De Narvaez, Ricercare 16 by Da Milano, and the pavane by Sanz.

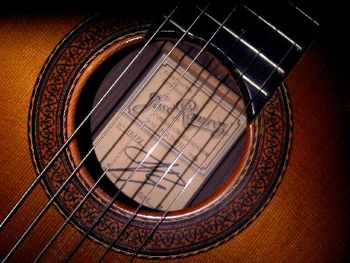

1991 Peter Barton

So I had the Ramirez. But I wanted something completely different. And this is what I have in this guitar, which I bought in London in 1991 (still very young age). This is an English guitar by luthier Peter Barton. I had the pleasure of visiting Peter a few years ago, and what a nice man he is. I bought the guitar for fifteen hundred pounds. It's worth many thousands more. It is a smaller guitar than the Ramirez, both in body size, and string length (650 mm).

This guitar is constructed of really fine wood. The top is European spruce, and the back and sides rare brazilian rosewood. Spruce is firmer than cedar, so at times this guitar can sound a bit bright. However, spruce has more sustain, and will produce a greater pallet of tones for a player who is expressive. The great Julian Bream always plays on spruce guitars, of a traditional style, similar to my Peter Barton.

This guitar was badly damaged on an airline flight. Peter masterfully rebuilt it for me. It came back louder, and with considerably more sustain. Impressive. It's really a fine instrument, but at times I have trouble controlling it's brightness. However, because it is a more expressive instrument, I've used it on more than half the pieces on this album. I think it did particularly well on Conde Claros, Ricercar 51 by Francesco Canova, and the De Visee minuets. This guitar can really sing.

Mid '70's Takemene

What? Takemene? Yes, this is a store bought guitar which my sister bought during college years. She did a good job. I think it would have cost about three hundred fifty dollars. That's all. But in a way, this is a gem of a guitar for it's extreme expressiveness. I recorded most of the De Visee suite on this guitar, because it was the only guitar available at Islay House, my dads's house, where I was visiting at the time. So I pulled it out, recorded in a fine sounding room, and I really think it held it's own. (And out-did it's expensive cousins in expressiveness.)

Yamaha SLG-130NW

How could I not mention the guitar that made this album possible? This is my 'travel guitar' that enables me to practice in hotel rooms. It's called a 'silent guitar', because there is no 'sound box', just a frame which comes apart to reduce travel size. Ah, but it's much much more. Previous travel guitars I had were pieces of junk. This guitar is a fine instrument all-round, and has the neck width and set-up of a classical guitar. I really think it is better constructed and designed than Yamaha's 'real' classical guitars. You just want to play this guitar. Thanks Yamaha, you really nailed it.

A final note on 'period instruments': I love hearing this music on the lute and vihuela. And I love it on the guitar equally. Bach on the harpsichord, organ or cembalo, the instruments much of his music would have originally been played on, is really lovely. But on the piano! Wow. How could I limit myself to the harpsichord original and ignore Glen Gould? To a certain extent any composer, even a lutenist plucking on his strings, operates at a higher level of creative consciousness that truly transcends the instrument. Playing lute music on the guitar is really not much of a stretch, because unlike the harpsichord and organ, which had no dynamics (no volume control by pressing a key softer or firmer like the piano), the lute and guitar are both dynamic instruments; the same left hand was fretting those strings five hundred years ago as they are today on a guitar, and those same human fingers were plucking those strings, lighter or harder, flesh or nail… They may have different accents, but these instruments speak the same language.

I am very fortunate to have stumbled my way into some really good guitar purchases early in my life. It started with the purchase, at age sixteen, of a 1972 Gibson Les Paul Delux at a mall in Savannah, GA. Somebody had traded it in for an organ, and the keyboard players in the shop didn't know what it was. Nor did I, at that age, because I thought $200 was a lot of money! My luck continued with a classical guitar purchase in the '80's, and one in the '90's, before good wood became scarce and prices escalated. A good concert guitar these days will go for at least ten thousand dollars. Over the years, I always assumed my guitars were just OK, compared to the amazing and rare instruments the pro's must be playing. Not so! Unbeknowst, I had made two very good guitar purchases in my youth.

1984 Ramirez 1a 'De Camara'

My first purchase, in London in about 1985, (when I was very, very young), was a 1984 Jose Ramirez 1a, 'De Camara' model. I paid one thousand pounds for this guitar. Yes, a lot of money! Well, it's worth many thousand now. Jose Ramirez is the most famous guitar shop, which defined the Madrid style: These are large bodied, heavy guitars with smooth sounding basses and good projection. They produce a dark, mysterious sound. My Ramirez has a cedar top, which gives it a nice warm sound. It is also unique in that it is a 'de camera' model. It has an inner shelf which adds clarity and separation to the notes. Little did I know when I bought this guitar, that it was the ideal Ramirez to record on, particularly for Renaissance and Baroque music in which polyphony can get lost in the moody depths of a standard cedar guitar.

For this album I used this guitar on the Dowland fantasia, the De Visee bouree and gigue, Fantasy XIV by De Narvaez, Ricercare 16 by Da Milano, and the pavane by Sanz.

1991 Peter Barton

So I had the Ramirez. But I wanted something completely different. And this is what I have in this guitar, which I bought in London in 1991 (still very young age). This is an English guitar by luthier Peter Barton. I had the pleasure of visiting Peter a few years ago, and what a nice man he is. I bought the guitar for fifteen hundred pounds. It's worth many thousands more. It is a smaller guitar than the Ramirez, both in body size, and string length (650 mm).

This guitar is constructed of really fine wood. The top is European spruce, and the back and sides rare brazilian rosewood. Spruce is firmer than cedar, so at times this guitar can sound a bit bright. However, spruce has more sustain, and will produce a greater pallet of tones for a player who is expressive. The great Julian Bream always plays on spruce guitars, of a traditional style, similar to my Peter Barton.

This guitar was badly damaged on an airline flight. Peter masterfully rebuilt it for me. It came back louder, and with considerably more sustain. Impressive. It's really a fine instrument, but at times I have trouble controlling it's brightness. However, because it is a more expressive instrument, I've used it on more than half the pieces on this album. I think it did particularly well on Conde Claros, Ricercar 51 by Francesco Canova, and the De Visee minuets. This guitar can really sing.

Mid '70's Takemene

What? Takemene? Yes, this is a store bought guitar which my sister bought during college years. She did a good job. I think it would have cost about three hundred fifty dollars. That's all. But in a way, this is a gem of a guitar for it's extreme expressiveness. I recorded most of the De Visee suite on this guitar, because it was the only guitar available at Islay House, my dads's house, where I was visiting at the time. So I pulled it out, recorded in a fine sounding room, and I really think it held it's own. (And out-did it's expensive cousins in expressiveness.)

Yamaha SLG-130NW

How could I not mention the guitar that made this album possible? This is my 'travel guitar' that enables me to practice in hotel rooms. It's called a 'silent guitar', because there is no 'sound box', just a frame which comes apart to reduce travel size. Ah, but it's much much more. Previous travel guitars I had were pieces of junk. This guitar is a fine instrument all-round, and has the neck width and set-up of a classical guitar. I really think it is better constructed and designed than Yamaha's 'real' classical guitars. You just want to play this guitar. Thanks Yamaha, you really nailed it.

A final note on 'period instruments': I love hearing this music on the lute and vihuela. And I love it on the guitar equally. Bach on the harpsichord, organ or cembalo, the instruments much of his music would have originally been played on, is really lovely. But on the piano! Wow. How could I limit myself to the harpsichord original and ignore Glen Gould? To a certain extent any composer, even a lutenist plucking on his strings, operates at a higher level of creative consciousness that truly transcends the instrument. Playing lute music on the guitar is really not much of a stretch, because unlike the harpsichord and organ, which had no dynamics (no volume control by pressing a key softer or firmer like the piano), the lute and guitar are both dynamic instruments; the same left hand was fretting those strings five hundred years ago as they are today on a guitar, and those same human fingers were plucking those strings, lighter or harder, flesh or nail… They may have different accents, but these instruments speak the same language.